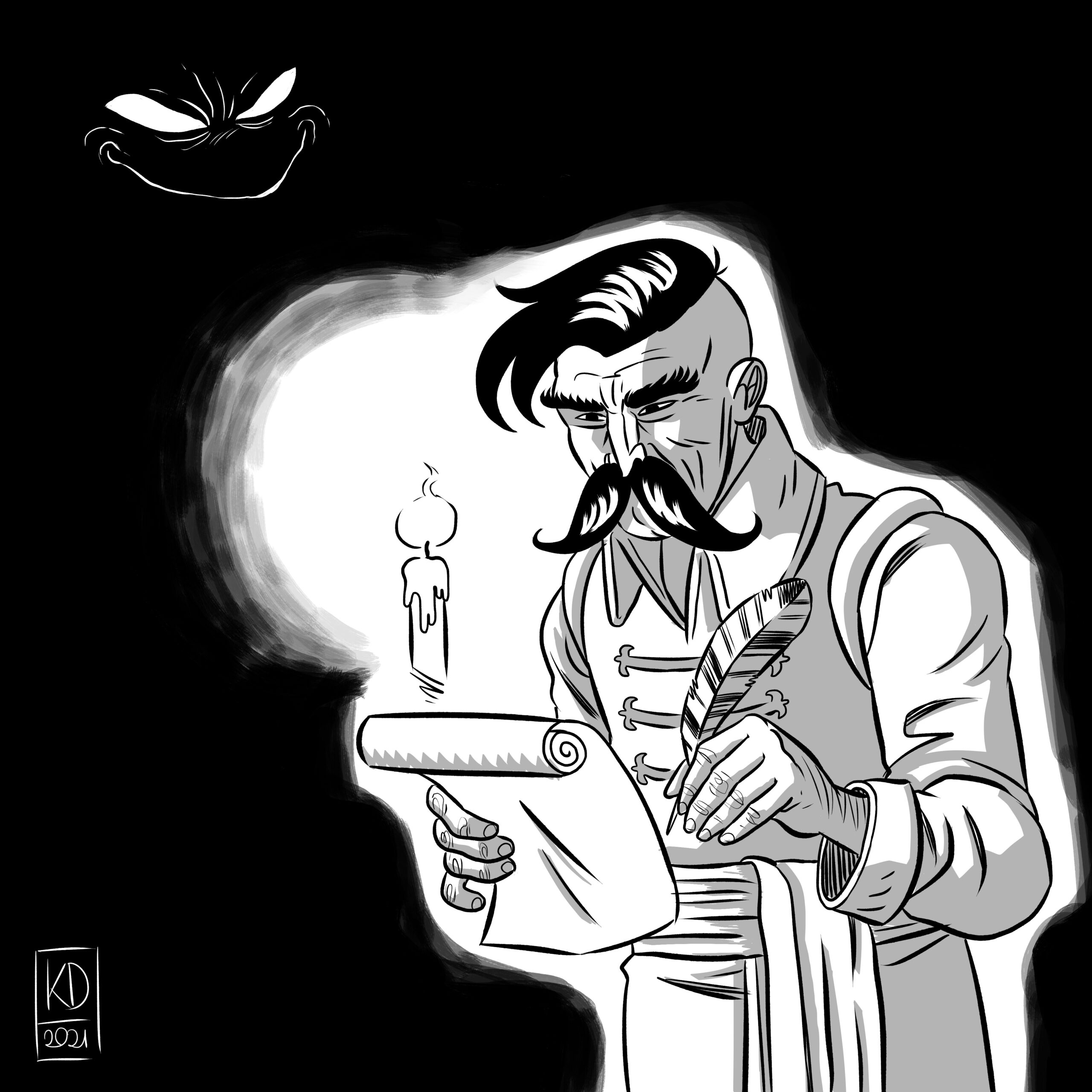

The management contract is a commitment that strongly binds the manager’s personal brand to the image of the company being managed. It creates a bond for better or for worse, stronger and longer than the contract itself, often in a way that is almost as risky as Master Twardowski’s bargain that was signed in blood. The unquestionable benefits in the form of fulfilling ambitions, personal development and attractive remuneration, always come at a price. Sometimes much higher than expected.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The management contract entails risks for the manager’s personal image. For some companies, the likelihood of such risks becoming materialized is lower, for others, relatively high. However, they must always be taken into account.

- The manager represents the company, voices its opinions and publicly functions on the same team with fellow directors or board members. Internal conflicts, or even the mere allegation of their existence, have a negative impact not only on the company’s image, but also on the personal brand of managers.

- The identification with the company’s mission, vision and values as well as the fulfillment of the expectations of internal stakeholders is an integral part of the contract. When there is a conflict between the owner’s vision and that of the manager, ultimately the former is always right.

- A manager will rarely have freedom of choice in selecting his or her team and must be able to build trust and cooperation with people he or she has only just met.

- One important part of the image of a professional manager is his or her conduct upon leaving the position.

“This inn is called Rome”.

The legend of Master Twardowski, which functions in several different versions, has inspired many Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and German authors. Perhaps the most famous work is the ballad by Adam Mickiewicz entitled “Pani Twardowska”, which is where the above subtitle quote was taken from. In addition to the ballad, there are folk tales, novels, operas, ballets, plays, films, comic books and even a special thread in The Witcher 3 that tell the story of the sorcerer. The character himself is sometimes linked to the authentic magician Jan Twardowski, who was active at the 16th century court of King Sigismund Augustus. However, the character shows a number of parallels with the German-born Faust, known from the works of Goethe or Mann, but already present in medieval fairy books.

According to the most interesting interpretation, the nobleman Twardowski sold his soul to the devil in exchange for great knowledge and command of magic, which brought him success, fame and wealth. He used the gift he had gained to the benefit of himself and others, including helping to cure the king’s love sickness. He was shrewd enough to add a clause to the pact stipulating that he would only give up his soul in Rome, where he obviously had no plans to go. Many years later, however, it was the devil who got his way, luring the self-confident gentleman to an inn called Rome and fulfilling the contract. The common need throughout all eras and communities for a happy ending resulted in the protagonist ultimately escaping an evil fate by hiding on the moon in all versions of the tale.

The character’s fate is most often analyzed in terms of its metaphysical and ethical aspects. From our point of view, what is most significant in the story is what connects the protagonist to the contemporary manager: the signing of a risky contract, obtaining the expected personal benefits, the care taken to avoid the pitfalls associated with the commitment, and the final, sometimes very painful settlement. We are not saying that every managerial contract is risky or that it resembles a pact with the Devil in the literal sense. We are merely pointing out the risks that always exist, although the likelihood of their materialization varies from company to company. This piece does not touch upon legal topics related to the manager’s personal liability under the applicable norms: we are focusing here on image issues only.

“I am the CEO, I do not have private opinions”.

This is how certain manager responded to journalists inquiring about her own opinion on a controversial issue, the circumstances of which indicated that differences between the official position and her private opinion were quite likely. This is the only correct approach, as a responsible manager represents the company and its point of view even when, or especially when, his or her personal views are different. The need to follow the company line is inherent in the essence of management. When choosing an employer, the manager naturally takes into account whether there is a consistency of values between him and the company as well as its key stakeholders. Having signed a contract, despite the lack of such consistency, may not only raise ethical questions, generate problems in the company’s communication with the environment, but also negatively affect the manager’s personal image and result even years later.

The temptation to keep one’s own opinions separate from one’s actions in a management role is common, especially among managers who operate alongside the scientific world. Situations where the practice of everyday life, a strategic ownership choice or the circumstances of a case require decisions that differ from textbook benchmarks are not at all rare. For practitioners with a scientific background, such dilemmas are extremely difficult, because – and here again I am quoting from a true statement by a certain chairman- professor – “you are a professor, and you only happen to be a chairman”.

The other aspect is when several functions are combined under the same person, which, while being related, generate the need for a different approach to certain issues. For example, the chairman of a large company, who is at the same time the head of a trade organization gathering competitors, must be able to clearly indicate in which role he expresses a given opinion. Another example: the chairman of a state-owned company, when asked about the government’s position on an issue that is inconvenient for the company. At all kinds of business congresses, it is quite common to observe characteristic moments of hesitation, or even the telling smiles of the speakers, when they are asked a question that has to be answered differently than they would have liked.

A specific kind of this dilemma is the transition of an actively working politician to a state-owned enterprise and adopting the role of a manager. Unfortunately, in Polish realities, it is far too often that the protagonists of such transitions fail to separate their roles, do not understand the essence of their new tasks, and de facto remain politicians, and thus almost always harm the managed company. It is difficult to consider such an approach in the context of managerial dilemmas, as these people are not really managers, so we will not analyze this topic in detail. However, it is worth emphasizing the opportunity that such a situation offers, in the case of distancing oneself from the political past. Some such individuals are able to use it effectively to build their own position in their new role.

Managing a company is always a team sport. A professional Board, however divided internally, must speak with one voice. The manager must therefore be aware that even if, in a closed circle of colleagues, he or she opposes a common decision, they will have to be in favor of it once it is out. The obligation to be beyond one’s own views, or even to present passionately an opinion of the board that contradicts one’s own point of view, should not cause internal dilemmas. If such a significant internal conflict arises, one should simply walk away. The “I don’t want to, but I have to” attitude in business is most often evidence of a lack of professionalism.

Everyone has a boss

The manager’s role is to convince his or her bosses – owners, shareholders, supervisory bodies – of his or her own vision for the company’s development. It is the highest level of trust and the possibility of pursuing one’s own idea of the company’s development that creates the optimal conditions for performance. Unfortunately, these are often not possible, and it is necessary to implement actions in the context of certain compromises, which are often profound. It is also extremely important to understand the type of organizational culture that is in place and the values that the company professes in the real, not merely declarative, sense. A responsible manager must be able to adapt his or her way of working to the conditions in which he or she operates. This does not mean abandoning the ambition to rebuild, strengthen or align the culture with the strategy adopted or the expectations of the environment, but it does mean choosing the right pace and plan for change.

Life, in which the element of randomness plays a greater role than most economists would like to see, puts companies in a variety of situations. The company is under constant pressure due to the dynamics of the competitive environment, the impact of the regulatory, political and financial environment and, from time to time, the extraordinary, unpredictable events such as the outbreak of a pandemic. In a situation of accumulated difficulties, there are greater than usual tensions between the company’s owners (shareholders, stakeholders) and its management. There seems to be plenty of disagreement over the direction of strategic change with the need for some owners to manually control the company. Since the old tried-and-tested principle is that if things go wrong in a company, either the strategy or the management must be changed, the manager’s choice here is limited: if he wants to continue to function, he must adapt. And this can give rise to the risk related to personal image.

As previously indicated, there is a special relationship between owner and management in state-owned companies. Here, the role of the key shareholder is played primarily by the relevant state body, but in Polish conditions it is also a group of political activists, most often empowered in an informal way and expecting to influence mainly human resources issues and the redistribution of marketing funds. A manager taking on their role of managing such a company must be aware of the existence of a wide range of informal stakeholders and have the ability to handle the needs they report, in a way that is as painless as possible for the company and their personal image as a professional. This means learning to function in an environment that has practices reminiscent of feudal relations rather than those associated with the standards of a developed organizational culture.

In the present period of implementation of the so-called active ownership policy by the state, a very significant influence of the state owner on strategic issues in enterprises is emerging. Different state institutions are taking over the role of supervisory and management boards when it comes to choosing the directions of development, operating strategies and even specific investments to be made. In extreme cases, state-owned companies are designated for purely political actions. This means an extremely difficult challenge for professional managers to combine owner expectations abstracted from economic reality with tough business, financial and legal conditions. The level of risk here is extremely high, hence the reduction in the number of professional managers in state-owned companies, and their place is taken by active politicians who do not understand or need managerial professionalism.

Human resources make all the difference

It is a truism to say that the quality of a company’s work is determined by its people, their competence, attitude and commitment. Building and motivating a team is always a manager’s most important task. The possibility of selecting staff at will is more or less limited. The “zero option”, meaning a complete replacement of senior management, is a rare and hardly optimal solution. More often than not, a new manager’s first task is to build a team based on existing human resources, complemented by a certain group of new, outward-looking people. It is essential to build the right relationship, understanding and trust between the new boss and his or her new team. This requires sensitivity, adaptability, compromise and sometimes ruthlessness. Since interpersonal relationships are at stake, not only competences but also emotions are on the line, and consequently the risk of resentment and trauma.

A manager must be able to build a strong organizational culture based on mutual trust, commitment and a desire to achieve common goals. He or she must be able to inspire, be an authority and a leader. This requires the highest level of influencing skills, building individual authority and the ability to see the needs of the people around them. A manager, even if he or she lacks “soft HR” talents, must develop them in themselves, acquire them or complement them with the support of good colleagues.

The manager is under constant critical observation. His immediate environment takes note of every detail: the color of his tie, his badly pressed shirt, the type of coffee he drinks and how often he has it, the way he speaks, his gestures, and so on. It is instantly known what the boss’s private life, interests, acquaintances and weaknesses are. Any departure from the abstract notion of the ideal is ruthlessly judged. The internal environment also expects the boss to adapt to their habits, way of thinking and working. This is another challenge for the manager, another point of the “pact with the devil’. It is necessary to understand the expectations of the staff, who on the one hand want a representative boss with a touch of class, and on the other hand they want a fellow person, who can take off his tie and make a joke at the right moment. The right balance of behavior, the ability to secure the acceptance of employees without losing authority, is an important element in building one’s own position and image as a professional.

A manager “is known by how he finishes”.

A paraphrase of a classic saying by a former prime minister is necessary, as the subject of this analysis applies to all managers, regardless of gender. Nevertheless, the issue of termination and the style in which it is done is extremely important from the point of view of a manager’s personal image.

Any management contract for a company is temporary by nature. No one is given the mission of managing a company forever, so being aware of this fact and having a strategy for leaving, is an important part of a manager’s professionalism. Taking offense at being dismissed, slamming the door or, as it also happens, leaving in a company car with company equipment and not returning calls for several weeks are behaviors that are beneath contempt.

A manager should leave in a respectful, polite and civilized manner. This means to hand over tasks, information and key issues to their successor, thank their teams and say goodbye to their closest colleagues. Organizations in which managers disappear as unexpectedly as they appear are weak and immature. You cannot call a strong, solid organizational culture in a reality in which someone with full authority one day disappears and is officially “forgotten” the day after.

The decisions made by a manager in a given company not only build but also weigh on his or her personal career. All elements of the actions directly influence the further course of his or her personal career. For some, there are new challenges, promotion and development, for others, the path ends there or becomes more difficult. A properly managed personal image enhances the opportunity for development. An unprofessional image generates the Master Twardowski effect: the need to “run for the moon”, i.e. change careers.

Sławomir Krenczyk