The energy crisis that is currently being observed in Europe is part of the war that Russia has declared on the West. In fact, the level of the continent’s dependence on energy supplies from Moscow is so high that Europeans may face shortages this winter, and that includes heat. Societies that have been accustomed to a fundamental level of living comfort for several generations have a difficult test ahead.

The shadow of war on European energy markets

As a result of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the European energy and heat market, so arduously developed, has been destabilised. It has come to the point where the Czech Republic, which holds the rotating presidency of the European Union Council, declared through its minister that the market is out of control and only takes negative factors into account, thus driving up prices. In fact, this view is not uncommon. By the end of August, the price of gas had exceeded even €300 per MWh, which is three times more expensive than in spring 2022. Gas, which is now the litmus test of Europe’s energy industry and the prices and availability of which determine the terms of the entire market, as it drives up the cost of electricity and, what is still not being talked about enough, also of heat.

For many years, the energy industry, including district heating, has failed to break through to the information mainstream, being left with its challenges in the niche of industry experts, outside the broader public attention. Today, that comfort no longer exists. First the volatility of initial energy media prices caused by Russia and then the aggravation of this trend by the aggression in Ukraine have led the world to be sure of only three things today:

The prices will go up. No one knows when we will reach a maximum price ceiling and whether such a “ceiling” limit even exists.

The fossil fuel deficit may last much longer than we assumed at the start of the war in Ukraine.

There is no clear idea of how this situation can be stabilised or when it might happen. We have therefore entered a state of permanent uncertainty.

The current situation has also made it abundantly obvious that it is always necessary to view energy and energy resources in terms of national security, on a par with military security, at the level of each state, union of states and the continent as a whole. This is how Russia has been approaching the issue for decades, following for years the business cooperation scenario with Europe in a model that today makes hydrocarbon blackmail possible. Moscow is well aware that this weapon could lose its effectiveness in the years to come due to the accelerating transition and the plan for Europe’s complete independence from fossil fuels by the mid-21st century.

By now, everyone should no longer doubt that Russia is fighting a war with the West, with gas, oil and coal as its weapons. The mysterious explosions destroying the Nord Stream I as well as Nord Stream II (which never became operational) at the end of September are yet another confirmation of what Moscow had already announced, namely that it would not restore gas supplies via the Nord Stream I (NSI) pipeline, which had a capacity of 170 million cubic metres of gas per day (55 billion cubic metres per year). Moreover, gas supplies to Germany via NSI had already been reduced by around 80% since June. By comparison, the Baltic Pipe project is a maximum of 10 bcm of gas per year, and Poland’s annual gas consumption in 2022 was just under 20 bcm per year. More importantly, Russia has explicitly admitted that the lack of supply is entirely the result of sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation for its aggression against Ukraine. On a positive note, sanctions seem to be having an increasingly strong effect on the Kremlin month by month as it goes to such lengths. The actions of Putin’s Russia should make it clear to Europe once and for all that this country is not and will never be a stable supplier of strategic raw materials – as they are treated as a tool to achieve political goals.

This is obviously having a negative impact on the energy market in Europe, especially Germany. Before Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the Federal Republic imported 55% of the natural gas it needed from the country led by Putin, and annually our western neighbours consume around 100 bcm of gas, which is five times more than Poland does. In recent months, Germany’s level of this dependency has fallen to 35%, and there have also been declarations of a complete end to raw material imports from Russia after diversification of supplies from other directions. This is a scenario that at the beginning of this year would have been considered interesting political fiction at best, because at that time the Nord Stream II project (a parallel to the NSI gas pipeline with the capacity to transport 55 bcm of gas per year) was close to being successfully completed and Germany’s independence from Russian this fuel was even greater. The current statements about Germany’s continued use of its coal power plants and even the extension of its nuclear power plants should be seen in the same terms. Unsurprisingly, Berlin is urgently seeking every means to plug the gas hole in its energy industry, which is affecting the market throughout Europe. A market that, prior to the Ukrainian situation, relied around 40% on Russian gas. According to Refinitiv, Russian gas pipeline supplies via the three main routes to Europe have fallen by almost 90% in the last 12 months.

for further analysis, go to ‘Russian warship, go …’ or the de-Russification of Europe’s energy industry

Transformational split

There is no doubt in anyone’s mind today that the long-term direction of transformation is zero-carbon, renewable energy sources and the complete elimination of fossil fuels. This is a very costly and lengthy process, but it is becoming the only way for Western Europe to permanently reject its dependence on fossil fuel imports from third world countries. In doing so, it was wrongly assumed that countries profiting from hydrocarbon exports would sit and watch the transition, operating within the demands of the Western customer, who says: give me a lot of your best product at the lowest possible prices now, because we want to give it up completely in a few decades or maybe even sooner. It was somewhat naïve of the West, and mainly of Germany, to think they would take cheap gas as temporary fuel, dictate the terms of the deal to Russia, and implement the Green Deal and the policy of moving away from hydrocarbons at the same time. If there was a strategic deal to ensure that Russia, as producer of energy resources, and Germany, as their distributor, had absolute energy dominance on the continent, then what we see today is the pursuit of Moscow’s true and hostile to the West objective as well as the fallacy of Berlin’s assumptions in this model.

In fact, the issue relates not only to gas from Russia, but also to oil, because it was difficult to predict that the Euro-Atlantic world could count on a lifebelt solution of lowering the price of a barrel on world markets. Thus, it may have seemed to Russia that it was entering its best period for re-establishing its superpower and aggressive policy towards its neighbours, and that it could count on German passivity in the energy business. Russia’s apparent deliberate upsetting the markets prior to the invasion and the resulting perturbations probably reassured Kremlin that the plan would work. This was even more so as NS2 was intended to further expand the possibilities of gas blackmail and turn the tables by pushing away Central and Eastern European countries, which had been natural transit states for Siberian oil and gas since the USSR.

Russia has therefore chosen a moment when the EU is performing a breakneck split over the precipice relying on very shaky foundations. One of them is the necessary evil of conventional energy and industry, dependent on fossil fuels, burdened by greenhouse gas emission charges (ETS). The other is the dynamic development of RES, still unable to guarantee the reliability of energy supply, requiring technological innovation and huge investments. At present, the balance cannot be maintained by either of these points . Moreover, the so-called ‘sustainable transition’ of the Green Deal for some countries means an accelerated revolution and very high social and economic costs. Unfortunately, the vision of a green future that has been pursued so far, implying more prosperity for the next generations, has turned into an extremely difficult challenge in February 2022 to secure basic energy supplies for Europe’s population and economy.

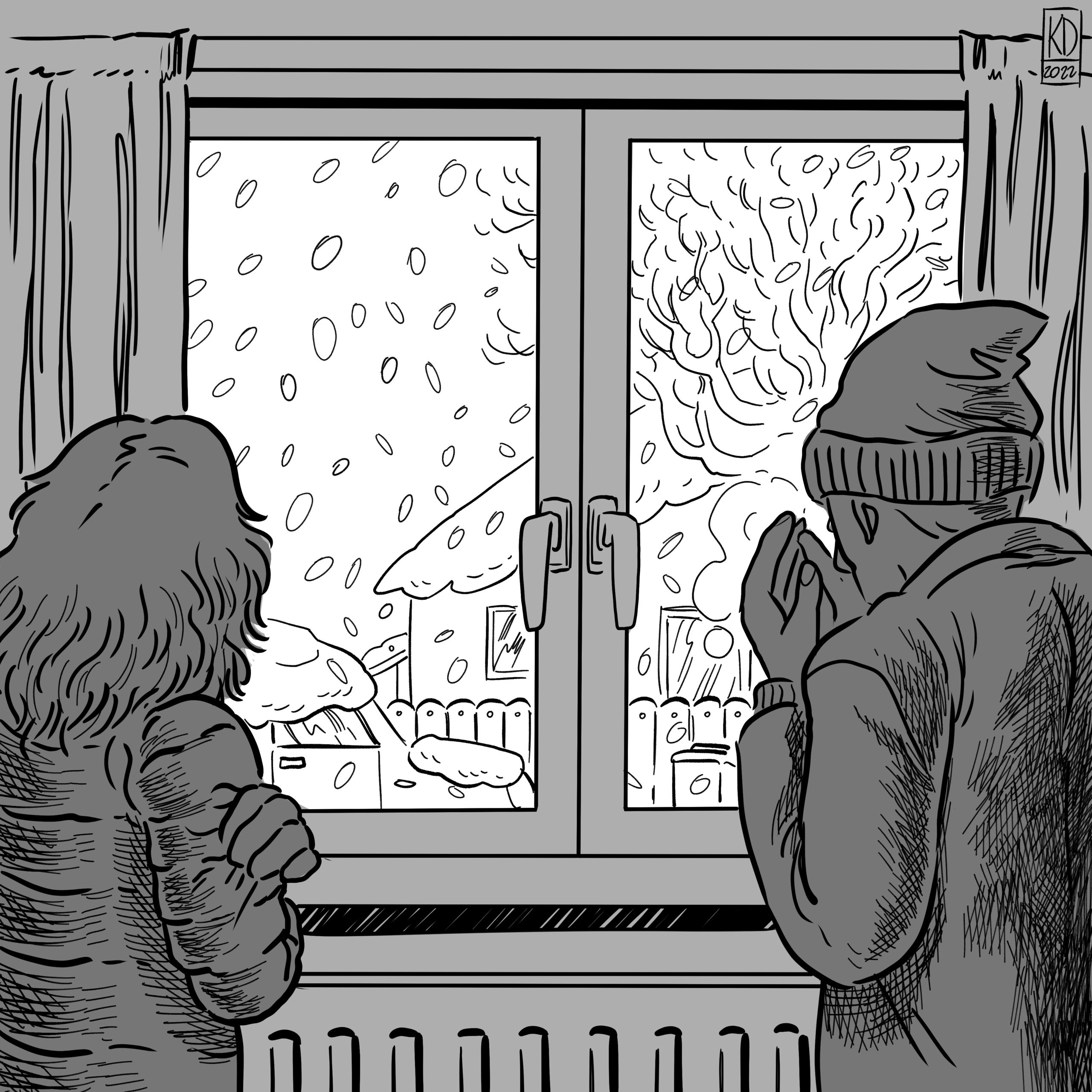

At present, no one can predict the extent of the coal and gas shortage in Europe and at what point it will occur . The situation is changing dynamically, not only through successive interventions, but also through fluctuations in demand, as the industry is reaching the point where the operation of some plants is becoming unprofitable through high gas or electricity prices, which are breaking new records from week to week. Prices fluctuate kaleidoscopically making any form of planning impossible. Another great unknown in this equation is nature, which in such cases does not always help, and in fact complicates matters. The weather can become a very important factor that will determine the scale of the problem Europe will face, as it has become increasingly difficult to predict in recent years. It is better to prepare for a cold and long winter than to optimistically assume that the weather will decide to help us. It is with this very unsettled condition that we enter the autumn/winter period of 2022/2023, a winter that may be like none before in Western Europe of the 21st century. A winter that will remind us that nor heat or electricity are given once and for all, and there may be times when hot water doesn’t flow from the tap and energy and heat join the category of luxury commodities

for further analysis, go to What if gas is not ‘transitional’ at all?

Overview of the district heating market in Poland

Poland is a specific country in terms of district heating. The growth of urban centres during the communist period, combined with the electrification of the country, led to the creation of many large district heating systems supplied with heat by large combined heat and power plants, i.e. producing heat and electricity at the same time, significantly increasing the efficiency of the entire process. In addition, the mass development of housing associated with prefabricated housing estates encouraged such solutions also in smaller urban centres, where district heating plants and boiler houses were built. The main driving force for the growth of heat sources in Poland was coal mined in Silesia during the communist era. The relatively simple accessibility of this fuel, combined with increasing extraction and a short supply chain, meant that the heat sector in Poland was built on hard coal. This dependence is still crucial.

Today, there are approximately 400 so-called licensed heating companies in Poland, Today, there are approximately 400 so-called licensed heating companies in Poland, with one company often serving several locations. Additionally, there is also a number of entities with installed or delivered power of up to 5 MW, i.e. those which do not require a licence. To illustrate the scale, the total length of district heating networks is approximately 22,000 km, which is more than half the length of the equator. System heat is used to provide energy to more than 15 million Poles, inluding not only homes, but also public buildings such as schools and hospitals. It is estimated that more than 40% of households across the country use the services of the district heating sector. These figures place Poland among the largest heating markets in the Union. In terms of the volume of annual heat sales, we can only compare ourselves with Germany.

Large district heating plants, combined heat and power plants (CHPP) and district heating systems are in the hands of several companies operating equally in the electricity market. France’s Veolia, which operates in Warsaw, Poznan and Lodz, and in total manages almost 60 district heating systems in 78 cities, is the largest player outside Poland. The Finnish Fortum is also present in Poland (e.g. in Częstochowa and Zabrze). Other companies are associated with state-dependent capital groups. These include PGE Energia Ciepła, Tauron Ciepło, PGNiG Termika, Enea Ciepło, Energa Kogeneracja (Orlen Group). The system is also co-developed by dozens of Municipal Heat Energy entities (MEC- Miejska Energetyka Cieplna) and Heat Energy Companies (PEC- Przedsiębiorstwa Energetyki Cieplnej) owned or co-owned by local authorities.

It is estimated that about 70% of the fuel used in district heating is coal and about 9% is gas. The remainder is, for example, RES, most of which is biomass, the supply of which is also complicated and more expensive after Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

for further analysis, go to Green industrial revolution as a gateway to a new deal for the European Union

The vicious circle of district heating

The case is particularly bad given that the heating sector was already in a difficult situation before. The industry’s strongest organisation, Izba Gospodarcza Ciepłownictwo Polskie, published a report in March 2020 entitled: “Ciepłownictwo bez środków na transformację” (“District heating without transformation funds”), pointing to the legal state and regulations as the main reasons for the accumulating problems. Heat plants were already claiming then that they did not have funds for investment at that time, which consequently led to a vicious circle – without funds they could not invest in transformation, but without transformation they suffer high costs of CO2 emission allowances, that currently are growing as dynamically as the prices of fuels, including coal.

What is more, there is a further transformational task for the heat area under EU law. Only energy-efficient systems will be able to survive, i.e. systems that use at least:

- 50% of energy from renewable sources or

- 50% of waste heat (heat generated in other industrial processes as a secondary consequence) , or

- 75% of the heat that is obtained from cogeneration, or

- 50% of the heat that is a combination of the above.

Most Polish systems, especially the smaller ones, do not meet this criterion or are only on the way to doing so.

Large plants, which are also the most efficient units, are responsible for a significant volume of district heat in Poland, as they operate on the basis of the cogeneration process and were significantly modernised after 1989. Cogeneration increases the efficiency of a unit by leaps and bounds, since two products are produced from the same unit of fuel ( hard coal), namely district heat and electricity. In a nutshell: a CHPP plant is a smaller-scale heat and power plant that uses the district heating network as a cooling system in the power generation process. Large-scale power plants use water from rivers, lakes, artificial reservoirs and cooling systems (e.g. giant cooling towers), while a CHPP plant has a heating network. This means that waste heat becomes a traded “commodity”. Hence the higher efficiencies of such plants.

At the other end of the spectrum there are medium-sized and small heating plants, most of which are owned by local authorities. These plants use coal only to generate heat and, in addition, their modernisation is often limited to the bare minimum i.e. dust extraction and sometimes desulphurisation. This makes these units inefficient and obsolete, leaving district heating systems at risk, as local authorities often do not have the funds to invest in new generation sources. Hence, we have the aforementioned vicious circle effect. Meanwhile, given current technological progress, even a small district heating plant can generate electricity using cogeneration, e.g. gas engine technology. This significantly increases the efficiency of the plant, and prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, additionally reduced costs, providing additional opportunities for the development and modernisation of district heating network sources due to access to EU funds and support schemes such as the cogeneration bonus. Yet, local authorities limited the capacity of installations where possible. Why? Because of the ETS system, which covers large installations, with a capacity of more than 20 MW. Exceeding the threshold results in the necessity to bear the cost of CO2 emissions, the price of which is currently more than €70 (over PLN 300) per tonne. The production of 1MWh of energy from coal means emissions of around 800 tonnes of CO2, and from gas around 400 tonnes of CO2. How to cover such costs, how to transfer them to the final consumer? So far, the European Commission has presented plans to freeze the prices of imported fuels, and the Polish government is responding by freezing prices for the end consumers. Such solutions are temporary and do not address the core of the problem. There are no plans to introduce ETS reform, which in the current situation may expose many consumers to structural energy poverty.

It is important to bear in mind that the heating sector is one of the most regulated economic areas, where the price of heat is determined by the regulatory body, which is the Energy Regulatory Office, and not by the company, which merely applies for certain prices on the basis of eligible costs. Lately, this is mainly about price increases and nothing is likely to change in this respect.

So far, investments in the heating sector have boiled down to replacing coal-burning plants with those using gas as fuel. This transformation, however, has been slow in Poland and we have not caught up with Western Europe. Naturally, facilities have been built in Warsaw’s Żerań or Stalowa Wola, as well as industrial CHPP plants in Płock and Włocławek, but the majority of system heat in Poland is still generated from coal, and this comes at the cost of high CO2 emission charges. However, it cannot be treated as an annuity of lagging behind, because in the case of Poland in the medium term, we have no way of skipping the gas stage in district heating. There is a lack of proven and appropriate technology which could substitute burning hydrocarbons in district heating on a massive, industrial scale here and now.

for further analysis, go to Hydrogen future or hydrogen illusions?

Deficit management

The issues that the heating sector faces are likely to affect many Poles and the country’s major urban centres. Therefore, all these challenges should be considered in the category of strategic national energy security. And the major problem at present is the price and availability of fuel for the autumn-winter season. It happens because, as mentioned, for years the dominant fuel for heating plants in Poland (approximately 70%) has been coal. Installations were upgraded and adapted to the tightening environmental standards, yet only in recent years have we witnessed the start of a greater number of investments changing fuel…to gas, regarded as a “transitional fuel” with sky-high prices on European markets.

In 2020, we imported about 12.9 million tonnes of hard coal into Poland, 75% of which came from Russia, which means about a 15% share of Putin-dependent raw material in our market. On the other hand, we imported about 17.4 bcm of natural gas, with 55% coming from Russia and 21% from Germany (which in fact means redistribution of Russian raw material), yielding a level of up to approx. 70 % dependence on supplies from the East. With the embargo on Russian coal, the Polish market therefore lacked a volume of coal equivalent to at least the annual production of a large mine. Such a gap cannot be filled by domestic mines, not least because of the long investment cycle associated with the commissioning of new mining longwalls, as well as limitations on the capacity of the shafts through which coal is brought to the surface. Another problem is logistics – the supply chains from the East based mainly on rail transport were interrupted practically overnight, and the remaining available import route is through both Polish and foreign ports, the capacity of which is also limited. Even if they were available, due to rail occupancy, availability of rolling stock, etc., the bottleneck remains in getting fuel to where it is needed.

The situation is likely to develop into a permanent shortage of coal on the Polish market, which will be difficult to compensate even with increased imports. It has become a problem to obtain the so-called coarser grades in particular, which are used by individual customers and for which some small-scale heating plants also compete on the market. It should also be noted that there will be no way to make up for such coal with domestic mining. Polish mines are currently focused on the extraction of steam coal, which goes mainly to system coal power plants in Poland. Perturbations in the supply market for this fuel are of fundamental importance for the heating industry, which used to consume about 5 million tonnes of coal a year, of which only about 2.1 million tonnes came from domestic mines and the rest was imported.

Despite being in a difficult situation, the large players have more leverage on the market, are able to restructure supply chains and negotiate with fuel suppliers. It is also difficult to imagine that one of the large CHPP plants, supplying one of the urban agglomerations, will shut down in winter, although such an apocalyptic scenario cannot be ruled out either. Should such a risk become reality, it may be necessary to transfer fuel at the expense of the power industry, combined with a partial shortage of electricity and the introduction of supply stages.

The situation is particularly difficult for smaller district heating companies that are not linked to the large conglomerates, which also lack specialised units capable of effectively importing coal from the other side of the globe. Smaller companies have little clout and are either underinvested or have switched to gas-fired boiler plants, which now causes additional problems with skyrocketing prices and the inability to realistically plan for the prospect of even the next season.

We should also bear in mind that the quality of the raw material is important, and that no two coals are the same, as was most clearly demonstrated by the case of recent weeks’ difficulties with Jaworzno’s power unit. Industrial installations are adapted to burn fuel with specific parameters. We should also take into account the fact that the coal ordered will not always be consistent with what is declared in the contracts – these are the laws of the energy crisis.

for further analysis, go to Polish atom and the energy transformation in the context of the European Green Deal

Europe’s hardest winter of the 21st century.

We are facing a challenge that Western societies have not tackled for a long time. We are weeks away from the first tangible signs of the crisis, reports of temperature restrictions in buildings, interruptions in gas supplies to industry and news of homes left without winter fuel.

In order to mitigate the effects of fuel shortages at socially acceptable prices, it will be necessary to intervene at state and EU level. The catalogue of such interventions is very broad, ranging from reductions in various taxes on energy, through direct subsidies for the purchase of energy carriers, to system price regulation, price freezing and the setting of limits on raw material prices. Mechanisms for systemic saving of energy, including heat, are also a necessity, in order to alleviate fuel shortages that cannot be replenished. It is fair to say that the market in the autumn-winter period will operate under the conditions of a war economy, it will be even more regulated and more strongly dependent on political decisions rather than market and economic mechanisms.

An emergency meeting of EU energy ministers was held in Brussels on 9th September. It was emphasised that gas and energy prices are at unacceptable levels and solutions must be sought to help not only individual consumers but also businesses. Some of the solutions proposed included a maximum price for imported gas, the issue of reducing energy demand, as well as special credit lines for energy companies as well as the redistribution of unexpected profits of fossil fuel-related companies. Bringing electricity prices closer to the cost of generation to affect consumers’ bills has also been suggested. Poland has also consistently pushed for changes to the ETS, including the introduction of a fixed ETS price of €32 for two years. More proposals are to be expected in the coming weeks, but for now it is unclear which ones can rely on EU consensus and implementation.

Advocating energy efficiency as well as encouraging control over the use of raw materials and fuel in daily life will be key over the coming months. In many cases, a rational approach to heat will be sufficient. Individual consumers who use their own heating systems (coal cookers, gas cookers, etc…) already have better habits in this respect. They do not need to be convinced that lowering the temperature by a degree or two results in real savings.

Among district heating customers, especially those living in unmodernised prefabricated blocks of flats, the approach to heating is still far from optimal. This is influenced by the fact that heating is paid for as a component of the rent, which is sometimes still averaged (due to the lack of a measuring system for individual consumption), that the entire heating season is billed as a one-off payment and that the heating companies are rewarded for the amount of energy produced rather than for the thermal effect on the customer. As a result, there are still radiators without temperature regulation and flats where the temperature is “regulated” by ventilating the rooms with the radiators turned on.

Today, taking measures on the consumer side that have the effect of optimising the indoor temperature while maintaining thermal comfort and generating significant savings is crucial. It is possible to plan for a 1-2 °C reduction in average temperature without adversely affecting people’s comfort, thus generating a real impact on the country’s fuel supply. The European Commission itself is calling for and encouraging a temperature drop to 19 °C as a response to possible gas shortages. These are the tasks for the public at this time of crisis, but it is also necessary to think about long-term solutions, i.e. increasing investment in energy efficiency and modernisation.

There are more and more unusual ideas for reducing the negative effects of the energy crisis across Europe. For instance, Finland is urging its citizens to think about how they use energy and which activities they can easily give up, replacing time spent with an electronic device to read an “analogue” book. The most gas-dependent countries go furthest with restrictions by introducing injunctions rather than casual appeals for citizens. In Germany, shop windows, monuments and billboards will be kept dark at night. There will be no hot water in some public buildings. France is also introducing a restriction on the use of lighting, and conceivably this will soon be the European standard. Heating in parts of buildings will also be limited in southern countries such as Italy, Greece and Spain. Economic and environmental peculiarities such as the use of air conditioning or heating with doors and windows open are also being eliminated.

Just a few months ago, calls for reducing temperatures in workplaces and even turning off heating in public facilities such as train stations would have been regarded as exaggerated, apocalyptic visions. Today, echoed by an increasing number of voices, they are becoming a sensible solution for the difficult times ahead. The acceptable minimum temperature for office or light manual work is 18 °C. Unless a top-down mandate is introduced, it is highly possible that companies themselves, in agreement with their employees, will lower the temperature or send employees to work remotely from their homes and flats, benefiting from basic forms of support in heating costs. The more creative commercial clothing entrepreneurs are already sending out offers to encourage people to purchase company fleeces and warm caps with logos to wear at the office.

Polish response to the crisis

Polish government has put forward temporary solutions to support district heating consumers. A top scale of increases that can be passed on to consumers has been given at a maximum of 42%. If the cost of generating heat is higher, the compensation is to go directly to district heating companies. The Ministry of Climate and Environment has calculated that the average support for a household, i.e. the amount by which the bill will be reduced, is between PLN 1 000 and almost PLN 4 000 over the entire heating season.

The solutions for private individuals with independent heating are much more controversial. Attempts to centrally regulate the price of carbon fuel have failed, the planned direct cash subsidies appear to be neither a realistically improving proposal, nor a fair or pro-environmental option. The government has announced a gas price freeze for 2023 as it did in 2019 with electricity. This is, of course, a solution for gas customers under a regulated rate, and will benefit households. What is also known is that there are plans to freeze electricity prices for residential customers consuming 2,000 kWh per year, however it is unclear what final shape the law will take on this issue and, as always, the devil is in the detail. The question arises about consumers who have made the costly effort of pro-environmental investments by installing, for example, heat pumps, mostly combined with photovoltaic installations, under the influence of government incentives, among others. In winter, PV installations operate for a short time, with little or no efficiency, and the electricity demand of heat pumps is high, exceeding the set limit of 2,000 kWh several times. This would suggest that the proposed regulations will probably not cover everyone, and that the philosophy of the solutions tends to promote passive behaviour, further penalising some consumers for their modernisation efforts.

Horrendous fuel prices will make energy poverty even more visible, thus increasing the role of the state in the energy market. Another negative, but hopefully temporary, effect will be a rapid deterioration of air quality. Unfortunately, the shortage of coal and its price will mean that old-generation coal-fired cookers, still operating in large number of households in Poland, will start to be fed with such crisis inventions as “rubber eco-pea coal” and other waste, which will lead to record smog levels in winter. This is a heavy blow against the clean air policy that has been pursued for many years, based on intensive efforts by the state and local authorities.

However, we must not succumb to the trap of easy solutions – subsidies and support mechanisms for households, and perhaps also for industry, are only a temporary emergency measures. An increase in prices may prove to be the most effective incentive to save energy, as well as an efficient approach to its daily use. Raising awareness rather than scaring should be the main reminder to save energy. All these elements should be included in the update of the “Strategy for the heating sector until 2030 with an outlook until 2040”, which the Ministry of Climate and Environment is working on.

Cold shades of the future

Unfortunately, all indications are that the winter of 2022/2023 will not be a one-off problem, followed by a return to the pre-war norm. We will probably have to get used to expensive energy and the perspective of fossil fuel shortages. That is why it is so important to use the next few months wisely, once the crisis lurking just beyond the threshold is over. After interventions such as subsidies for electricity, gas, heat, coal, biomass, etc., emergency fuel imports, ad hoc patching up of emerging gaps and problems, the time will come for prospective action. Simply because no country’s budget will be able to bear such expenditure in the long term. The expenditure that also has a pro-inflationary effect and increases the national debt.

Investments in heat and power are time and capital-consuming and require planning that ensures the supply of energy, heat and hot water to consumers in a systemic way. This cannot be done overnight, introducing changes immediately before winter is unrealistic, and the transformation of existing sources should be planned and system-based. Above all, it should take into account the role of gas, adjusted for the current political and market turbulence. The largest district heating companies have announced a number of investments in cogeneration sources based on CCGT technology (gas-steam blocks ensuring the most efficient production of heat and electricity), such as Grudziądz, Poznan, Gdansk, each of which will require more than 500 million m3 of gas annually. This will, of course, significantly increase the demand for gas, not to mention the purely power generation projects of the Dolna Odra or Ostrołęka gas-fired power plants and the industrial demand for gas, with Grupa Azoty as the largest consumer, which uses around 2.3 billion m3 annually.

The future role of gas and maintaining its role as a transitional fuel depends on the European Union actually diversifying its sources of supply rapidly and becoming independent of Russia by building an appropriate number of LNG terminals, gas connections between countries (such as the Poland-Slovakia interconnector opened in August), gas storage facilities and similar infrastructure. In addition, it is necessary to obtain an adequate volume of supply from producers, which means reconfiguring global markets. The EU perspective has been intentionally pointed out, as it seems that diversification of Polish supplies is not enough. What is also needed is a sufficiently stable and low gas price. In this scenario any new gas investment in the country should anyway be considered in terms of the actual possibilities of importing gas to Poland, so that we do not tighten the gas noose around our neck ourselves by building sources the capacity of which will have to be curtailed because of the price of gas or lack thereof, as is currently happening in Western countries.

The current development of RES does not allow the replacement of large district heating sources with renewable energy. The capacity of such solutions is too small or too unstable or simply inefficient. Also, hydrogen, which has become popular in recent years, is for the time being a matter of the future. A promising technology that would solve the dependence of district heating on hydrocarbons is modular nuclear reactors, the so-called SMR (Small Modular Reactor) or MMR (Micro Modular Reactor). However, the maturity of this technology will have to wait at least a few or several more years, and the Polish district heating industry is forced to modernise now – not only because of EU legislation and the dynamics of geopolitical change, but also because of the advanced age and exhaustion of coal-fired installations.

In the long term, it is important to think about changing the heat market in Poland so that it rewards energy efficiency not only on the part of consumers, but also on the part of heat suppliers and producers. Today, the more heat plants earn, the more they can sell. It does not matter whether there is an increase or decrease in the number of consumers, nor whether this heat is discharged through open windows, used in production halls or in public buildings which have not undergone thermal modernisation. This results in inefficient use of fuels, i.e. the coal and gas that are currently in short supply on the markets. It also results in increased CO2 emissions and the costs of doing so. Changing the financial model so that the heat supplier is rewarded for efficiency and the thermal comfort of the consumer could be a solution. In other words, moving away from the simple assumption that the more heat you produce, the more money you earn. A vision of such a model for the future was proposed a year ago in a study by the Energy Forum. According to it, district heating companies could be rewarded for providing the thermal comfort they contracted with the customer. This opens up room for heating plants to increase profits by reducing heat production – the fewer units needed to realise thermal comfort, the more money the “PEC” earns. The way to achieve this is through a programme of modernisation towards energy efficiency not only of heat sources and networks, but also of consumers.

Another solution to the heat and electricity problems of the future could be distributed energy, which will strengthen Europe’s resistance to hydrocarbon blackmail. Today, we can not only imagine, but implement the construction of the future, where new buildings will be self-sufficient in terms of heat, cooling (air conditioning) and electricity. The technologies are available on the market, but prices and habits of existing standards are sometimes barriers to widespread use. A positive example of overcoming limitations is the Szczytno housing community, which decided years before the crisis to disconnect its ordinary block of flats, one of many in Poland, from the local coal-fired boiler plant because the costs were too high. The residents opted for renewable solutions: solar collectors, heat pumps and photovoltaic installations on roofs and balconies, so that the building would become energy self-sufficient. Today, this is more of a fun fact than a common solution, but with the development of technology, including efficient and economical energy storage, as well as fail-safes, the direction seems interesting.

Conclusion

- No one can guarantee today that there will be no shortage of gas in Europe in winter. The likelihood of a scarcity of other energy carriers (including hard coal, which is crucial for district and individual heating) is also real. The risks of restrictions or even temporary cessation of energy supply must be taken into account.

- The deficit of energy carriers should be regarded as a permanent phenomenon, lasting beyond the forthcoming autumn-winter season. It will have a long-term impact on electricity and heat prices, affecting economic development and exacerbating fuel poverty.

- We are facing radical decisions to reduce energy consumption at European Union and Polish levels. Action is needed to change consumer habits: savings in energy use should be made in all possible areas. A realistic scenario is the reduction of heat supply to industry (including temporary full shutdowns) and limitations on supply to individual consumers (reduced thermal comfort). The consequence could be a return to remote working/learning model used during the pandemic period.

- Alongside ad hoc measures, it is necessary to introduce solutions to accelerate the energy transition, in particular for the district heating sector, which is burdened by systemic problems.

- The struggle against the energy crisis caused by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is also a struggle to maintain social peace. Scenarios of a “European winter of all times” and mass protests fuelled by Kremlin agents are unfortunately a plausible possibility. From this perspective, the energy crisis will also challenge the contemporary model of democratic states.