In the European Green Deal, gas is identified as a “transition fuel’, a temporary replacement for coal on the way to climate neutrality. The plan is for gas to disappear in 2037, once its role has been fulfilled and new hydrogen technologies have been developed, in the same way that coal is disappearing today. However, what will happen if the new technologies fail to meet the expectations in terms of cost, technology, environment and securing the continuity of energy supply under all conditions? How long will this “transitional period” last in reality? And is it possible that both the ongoing and planned huge investments in gas infrastructure are calculated for only 15 years?

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Green Deal is about the development of renewable or hydrogen-based solutions that will make the European continent, and possibly the whole world, completely independent of coal and other fossil fuels by mid-21st century.

- Gas appears to be the ideal temporary option for the period of refinement and commercialization of the technologies expected in the future. Stable, weather-independent gas-fueled units that produce energy flexibly in response to demand, emit far less CO2 than their coal-based predecessors.

- A gigantic expansion of gas infrastructure is in progress, the future use of which as a hydrogen infrastructure is questionable.

- It is also difficult to predict the economic and technological efficiency of future hydrogen-based systems. A large part of the necessary solutions still requires developing.

- It is therefore quite likely that during the energy transformation, the “transition fuel” will remain in Europe and the world for much longer than is being declared today.

Europe 2050

We can also see the new technological and industrial revolution in Europe that we will be facing in the coming decades as a great social and civilizational experiment, designed to drive economic development and foster research and development on an unprecedented scale. The result, in line with the EU strategy, will be a complete transformation of the economic model and thus the structure of markets in many sectors, as well as business models and consumer behavior. And indeed, we are witnessing the emergence of new solutions proposed both in start-up models and within large corporations, following political declarations at various levels, as well as mechanisms supporting accelerated technological development. There is ongoing work on effective energy storage, digital solutions to adapt the network to the requirements of a distributed structure, new technologies for heat and cooling production, as well as “green” transport, emission-free steel and chemicals production. For the time being, many of these solutions exist as concepts or prototypes.

It is still a long way from to the commercialization of the solutions that are crucial from the point of view of the technological revolution. Meanwhile, there are very real, large-scale “transition” projects being implemented: the development of transmission infrastructure for traditional gas, the construction of generation sources based on this fuel and an attempt to eliminate stable, competitive energy sources such as nuclear, biomass, geothermal or highly efficient coal sources. To paraphrase an old saying, the gas “bird” will be held firmly in Europe’s hand, while a climate-neutral “two in the bush” are so far a vision that at the present stage of technological development is rather out of reach and and those two proverbial birds are merely balancing somewhere in a distant bush.

It is likely that with the regulatory mechanism set in motion on an unprecedented scale, along with various support programs and EU funds will result in the further development of technologies and solutions for renewable energy sources, energy storage, the production of green hydrogen and so on. Nevertheless, it seems premature to dismiss the idea of gas fuels today. This is because, in addition to its importance in power generation, partly due to its ease of use and low failure rate, it is also an important raw material for other industries such as petrochemistry and fertilizer production. We should also bear in mind the growing demand of households, including for heating purposes. Moreover, the export of gas is an important component of national income for many world economies. Thus, on the one hand, we have ambitious goals of the leaders of developed Western countries, on the other hand, there are the interests of such economies, countries and societies, as well as their potential resistance to pushing the goal of eliminating gas in the medium and long term.

„Star Wars”

In March 1983, American President at the time, Ronald Reagan, announced in his speech to the nation the construction of a strategic missile defense. The program, designed against the USSR, was officially named the Strategic Defense Initiative, but it went down in history as the “star wars” program. It was the peak and turning point in the US-Soviet arms race that had lasted for more than three decades. The competition taking place on all continents and in space was of a political, military, economic and technological nature. The announcement of placing in orbit a combat satellite system capable of shooting down even the most advanced enemy ballistic missiles in any part of the planet tipped the scales in favor of the US in the fight for world domination. The Moscow “empire” surrendered, mainly in economic terms, allowing many countries to break free from its supremacy. To the best of our knowledge, plans for the Strategic Defense Initiative, including the installation of combat systems and satellites, were not fulfilled, but the arms race left a number of useful technologies that we still use today. The conclusion is clear: the most important result of launching the arms race in space was that the US reached economic domination on Earth. In the long term, the overall result of several decades of the arms race is the strengthening of the US political and military position in the world, the technological leadership of Western companies and unimaginable profits from the commercialization of military solutions such as the internet, satellite navigation, digital telecommunications, modern materials and nuclear power plants. To put it in a nutshell, the implementation of the program’s objectives was not necessary to achieve its most important goals.

Can the European Green Deal operate in a similar manner? Who will benefit from it on a European, regional and global scale? What if the EU’s climate neutrality, accomplished through renewables and the digital technologies that support it, turns out to be merely an attractive vision to reconfigure the continent’s economic structure, remove the competition that unattractive technologies pose and, in the process, drive the development in a different area? What if in 10-15 years” time, after carbon (and perhaps nuclear) technologies have been replaced, it turns out that a conventional, stable basis for the electricity system is still necessary?

Gas today, green hydrogen tomorrow

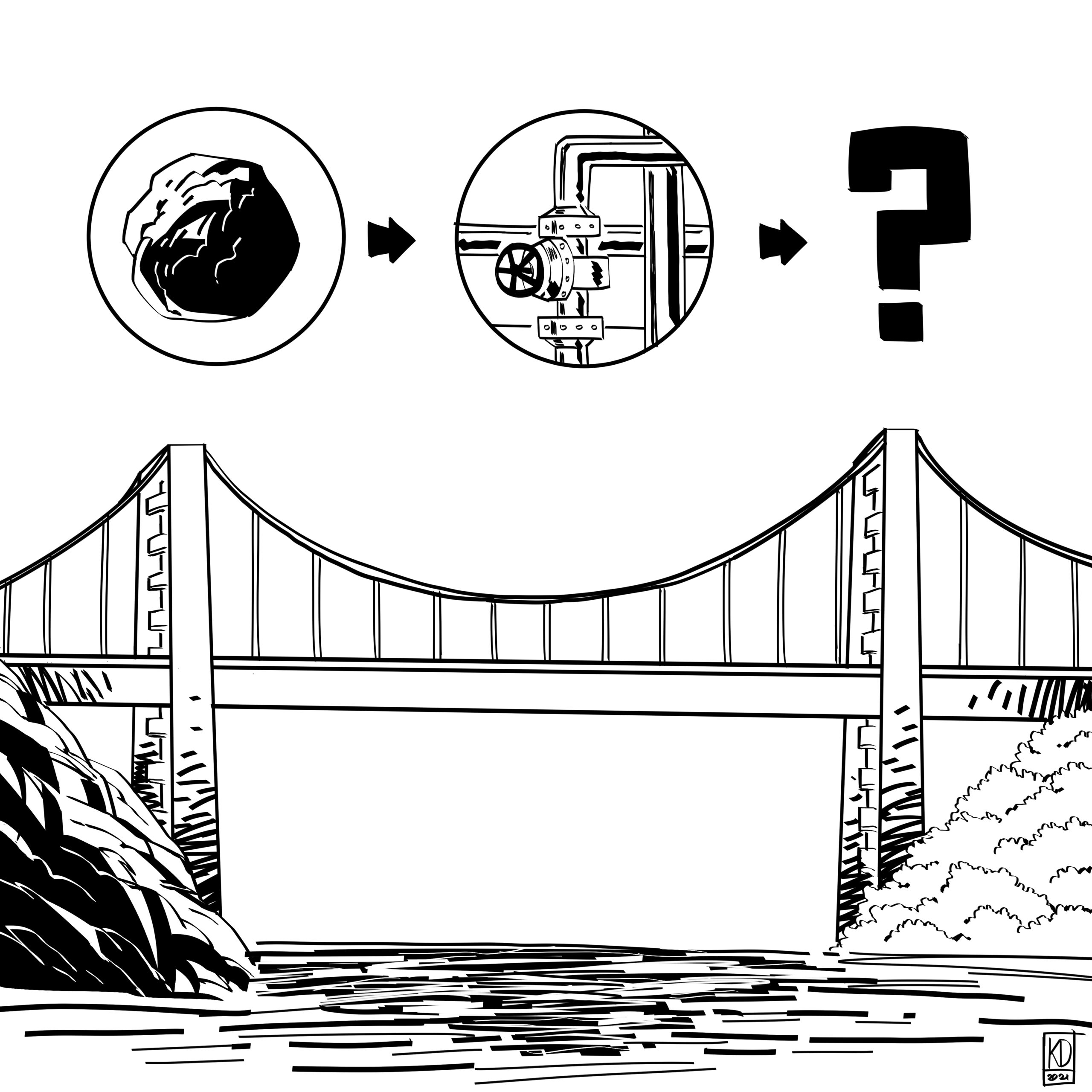

Alongside the extraordinary growth of investment in renewable energy sources, there is a gigantic expansion of gas infrastructure in progress. Massive gas pipelines are being built, directly connecting Russian gas deposits with the German and then the European market. Once Nord Stream 2 has supplemented the transmission capacity of the NS1 pipeline (twice the amount of 55 bcm of gas from Siberian deposits), it will be possible to supply more than half of Europe’s total demand for the blue fuel. Its further distribution by means of the recently established OPAL and NEL branches, as well as the planned 63 bcm capacity of the next South Stream pipeline, will strengthen the role of the Russian-European (mainly German) partnership in the European market, and increase the competitiveness of gas as a fuel for more than just the “transitional” period. At the same time, gas distribution networks are being intensively developed, the capacity of inter-connectors between countries is being improved, and new gas-fueled power and CHP plants are being planned. In a nutshell, the expansion of the gas ecosystem in Europe is proceeding in a manner that is characteristic of a long-term plan of its use. It is hard to imagine this trend slowing down and new investments being deconstructed as early as next decade.

As a supporter of the implemented solutions would say, it is not surprising at all, since having abandoned natural gas, this new infrastructure will be useful for the transmission of green hydrogen. This “reassuring expert side-trend” is a vision that has been picked up by the media and has become one of the convenient arguments used to promote the European Green Deal. Admittedly, it is not a scenario written down directly, but it is being considered by the media with all due seriousness: after the completion of the transitional fuel phase, i.e. after 2037, the gas transmission infrastructure that has been built and is still being developed would serve the use of hydrogen ( green only, obviously). Unfortunately, from the point of view of today’s technical capabilities, this seems questionable, very risky or unreasonably expensive. Even though the fuel of the future, i. e. hydrogen, is not the subject of this article (a separate text will address this), for the purposes of this argument, it is worth casting doubt on the feasibility of effectively converting gas infrastructure to hydrogen. The completely different properties of the two fuels mean that most existing natural gas installations are unlikely to meet the relevant requirements for leakage without a very deep and highly costly upgrade. Therefore, it is also difficult to imagine the point of possibly replacing the systems under construction on such a large scale in just over 10 years” time.

Europe 2037

With the European Green Deal in mind as well as the urgent need to eliminate coal sources, gas seems to be the best possible, proven and least painful ( in terms of emissions and costs) route to a fair transition and to achieving climate neutrality, especially in a situation in which our country has been given real, economically viable opportunities to diversify its supply. These include: the LNG port in Świnoujscie, an option to supply gas from the Norwegian shelf, the launch of the Baltic Pipe gas pipeline in the timeframe of 2022, or the project to build a Floating Storage and Re-gasification Unit (FSRU) LNG terminal in the Bay of Gdańsk. Currently, it seems that the main task in the transformation of Poland’s energy mix should be to design and transform the “coal-to-gas” shift in the way that would prevent the over-dependence of the energy sector on that fuel as well as a similar repetition of the social costs we are suffering due to the withdrawal from coal. To put it bluntly, this is necessary so that in 20 years” time we don’t have to sign a social contract with gas workers the way we have to do with miners today.

Meanwhile, there are ongoing investment processes outside our western border that could result in redundancy of sources and, consequently, an oversupply of energy. A strong coal base, nuclear power plants that are still in operation and the development of a gas infrastructure based mainly on Russian crude provide a solid basis for the development of renewable sources. In the longer term, this could mean the possibility of increased consumption of “transitional” gas fuel should the entire European economy not be rebuilt in time in the shape and direction indicated in the Green Deal. This may happen for a number of reasons. For example: new solutions may prove insufficiently resilient to threats to the security of energy supply, the results obtained from the application of new technologies may prove disappointing, and business models and projects may fall below the intended cost-effectiveness. Finally, energy price increases may turn out to be higher than the one that is either socially acceptable or guarantees the competitiveness of the European economy.

One should therefore reflect on whether, in the case of the Green Deal, we are not dealing with a project which, in addition to the official “Plan A’, also has a number of alternative scenarios embedded in it, including one which involves the use of gas in Europe over a much longer period than that officially planned by European climate-neutral strategists. In that case, this “temporariness” and “transience” of gas could turn into the foundation of European fuel-energy security. It is not difficult to guess who will benefit most from this.

The World of 2050-2060

Considering this article, it is worth noting that the vision of the European Green Deal has the potential to spread to other regions of the world. This is a tremendous challenge, but the first and firm steps in this direction are already being taken. The change of the US president has brought about a change in the climate policy approach of the world’s major power. One of Joe Biden’s first decisions was to “unfreeze” the Paris Agreement, a treaty that had been “frozen” since 2015 because it had not been ratified by the world’s major powers. The declaration made by China, the world’s biggest polluter, that it intends to achieve climate neutrality as early as 2060, is also crucial. The recent climate summit organized by the US administration in April 2021 indicates that the expansion of the European Green Deal guidelines and objectives is gaining momentum and has the potential to become a political and economic perspective for most countries in the world. Who will be the biggest beneficiary of this comprehensive programme? At this stage, it is only possible to speculate, but in the next few decades we should be able to estimate more precisely what the profit and loss balance is with regard to the strategy pursued to achieve climate neutrality for the world’s most industrialised economies by the middle of the 21st century.